くらしのセンター・DAN HOUSE 浜松店 Living Center・DAN HOUSE Hamamatsu Branch

くらしのセンター・DAN HOUSE 浜松店

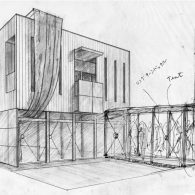

多摩美術大学の建築科を卒業と同時に自身で設計を行った中村高淑の処女作。実家および自身の住まいでもある住宅部分と家業のインテリアショップの店舗を併設する建物である。

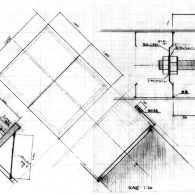

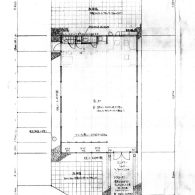

ローコスト・ハイデザインをコンセプトに厳しいコスト制約の中で、スケルトンは構造認定を取得している地場の軽量鉄骨系プレハブ倉庫メーカーの躯体フレームを流用し、インフィルとしての内装や外構などとは分離して、それぞれ主要な専門職を一時的に直接雇い入れ、施主直営工事として自身で直接監督し発注した。徹底した内製化などのコストダウンを図ることで、店舗用の特注の内装什器まで含めた総工事費で「 40万円/坪 」という、当時としても驚異的な超ローコストを実現することができた。

倉庫用のシンプルな躯体をベースに基本的には廉価な材料の組み合わせにより仕上げたが、インテリアショップとしてはいかにも安っぽい印象を与えないようにと工夫した。

具体的にはガルバリウム鋼板やアルミの庇やバルコニー、鉄といったシャープな金属素材を用い、シンメトリーを基調にしたリズムで格調の高さを与えつつも、エントランスアプローチ部分はあえてずらして配置、さらに木造の柱に軽やかな鉄のフレーム+膜屋根を乗せ、やわらかな質感の対比構成によって、権威的になりすぎたり単調さを避けるために、最大限のコストパフォーマンスを得られるよう計画した。

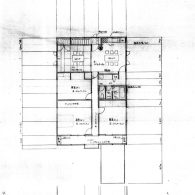

1F、2F共に軽量鉄骨の構造柱はバルコニー下部のショーウィンドウ的な展示スペース以外を除き外周部のみに設置、つまり短辺方向9.000m・5軒間口(1軒=1800)を無柱空間とすることで、長い将来にわたりフレキシブルな室内レイアウトを可能にする。

学生時代に設計事務所や内装業者でのアルバイトでの設計や現場経験があるとはいえ、大学卒業してすぐのことで右も左もわからず、何案か考えるもことごとく予算に会わずに概算見積段階でボツになる。

このような紆余曲折があったもののたまたま建設地の数ブロック先に倉庫屋さんがあったことでカタログや実例をみせてもらい、スケルトンインフィルによる分離発注の手法を考えついたこと、さらにたまたま内装業に関係して職人のつてもあったことで予定よりもむしろ安価な着地点にたどりつき、完成にこぎくことがでいた。当初イメージしたものからはかなり割り切った案になったとはいえ、こうして自身で考えた初めての建築が目の前に現れた時にはたいへんな感動を覚えた。

実は家業を継ぐつもりで新築したのが、この自宅兼店舗の建設の結果、あらためて建築設計の道に進みたいと強く思うようになり、数ヶ月後には上京して、母校である多摩美術大学の研究室を訪れることになる。縁あって田淵教授(当時は助教授)の主宰する設計事務所と数年後には母校多摩美キャンパス設計室に出向し、数々修行を積ませてもらい、独立への足がかかりを掴むことになる。

バブル崩壊後の長引く不況と父親の死去もあって、すでに建物は売却したのだが、今現在(2020年時点)でも飲食業の店舗として長きに渡り使われ続けている。

親不孝ではあったが、建築家として今日があるのもこの一作目の忘れがたい経験があるからこそだと思い、機会を与えてくれた両親には感謝したい。

竣 工 1993年

所 在 静岡県浜松市

構 造 軽量鉄骨造

延床面積 242.06m²(73.22坪)

敷地面積 283.00m²(85.60坪)

95年浜松市店鋪コンクール優秀賞受賞

Living Center・DAN HOUSE Hamamatsu Branch

This building is the debut work of Takayoshi Nakamura, who designed it upon graduating from the Department of Architecture at Tama Art University. It serves as both a residence—his home and family house—and a store for the family’s interior design business.

With the concept of “low cost, high design” in mind, the project was built under strict budget constraints. The skeleton was repurposed from the structural frames of a local lightweight steel prefabricated warehouse manufacturer, which had obtained structural certification. The interior and exterior elements, treated as infill, were kept separate from the skeleton. Key specialists were temporarily hired directly, and the project was managed and contracted directly by Nakamura as an owner-directed construction. Through rigorous cost-cutting measures, including extensive in-house production, the total construction cost—including custom interior fixtures for the store—was brought down to an astonishingly low price of ¥400,000 per tsubo, an exceptional achievement even for that time.

The building was primarily finished using a combination of cost-effective materials on top of the simple warehouse framework. However, careful design considerations ensured that it did not appear cheap, as it housed an interior design store. Specifically, sharp metallic materials such as Galvalume steel sheets, aluminum eaves and balconies, and iron were used to establish a refined rhythm centered on symmetry. At the same time, the entrance approach was intentionally offset. A wooden column structure was combined with a lightweight steel frame and membrane roof, creating a contrasting softness. This approach maximized cost performance while avoiding an overly authoritative or monotonous design.

On both the first and second floors, lightweight steel structural columns were positioned only around the perimeter, except for a showcase-like exhibition space beneath the balcony. This allowed for a column-free interior space spanning 9 meters along the short side and five modules wide (one module = 1.8m), ensuring flexible room layouts for years to come.

Despite having some experience in design and construction from part-time jobs at architecture firms and interior contractors during university, Nakamura was still fresh out of school and unfamiliar with many aspects of the field. Several design proposals were scrapped at the preliminary cost estimation stage due to budget constraints. However, by chance, a warehouse company was located just a few blocks from the construction site. After reviewing catalogs and examples, he conceived the skeleton-infill separation method for phased contracting. Additionally, connections with interior construction professionals helped secure lower costs than initially expected, making completion possible.

Though the final design was significantly streamlined compared to his original vision, the moment his very first architectural creation materialized before his eyes was deeply moving.

Originally, this home-and-store project was intended as a step toward taking over the family business. However, the experience of designing and building it reinforced Nakamura’s strong desire to pursue architecture professionally. A few months later, he moved to Tokyo and visited his alma mater, Tama Art University, to further his architectural education. This led to an opportunity to train under Professor Tabuchi (then an associate professor) at his architectural firm. Eventually, he was dispatched to the Tama Art University Campus Design Office, where he gained valuable experience, paving the way for his independent career.

Due to Japan’s prolonged economic recession following the burst of the economic bubble and the passing of Nakamura’s father, the building was later sold. However, as of 2020, it continues to be used as a restaurant, demonstrating its lasting functionality. While he acknowledges his actions may not have fully honored his family’s expectations, Nakamura remains deeply grateful for this unforgettable first project, which played a crucial role in shaping his career as an architect. He expresses his sincere appreciation to his parents for the opportunity they provided.

Completion: 1993

Location: Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka Prefecture

Structure: Lightweight Steel Frame

Total Floor Area: 242.06 m² (73.22 tsubo)

Site Area: 283.00 m² (85.60 tsubo)

- 竣工

- 1993年

- 所在地

- 静岡県浜松市

- 構造

- 軽量鉄骨造

- 延床面積

- 242.06m²(73.22坪)

- 敷地面積

- 283.00m²(85.60坪)

photo by